Drawing on Devotion:

The Great Synagogue of Aleppo in Ink and Paint

A Sanctuary Through Time

For over twelve centuries, the Great Synagogue of Aleppo — also known as Kanīs Ḥalab al-Markazī (كنيس حلب المركزي), the Al-Bandara Synagogue, or the Central Synagogue of Aleppo — stood at the heart of the Syrian Jewish community, one of the most enduring and vibrant in the Middle East. This spiritual center served not only as a house of prayer — but also as a stronghold of tradition, a sanctuary in times of upheaval, and the guardian of the Aleppo Codex. Throughout its existence, the synagogue fostered the evolution of the unique Musta’arabi rite of Aram Ṣoba, welcomed Sephardic exiles, and survived the turbulence of conquests, a short-lived conversion to a mosque, riots, and wars.[1]

Rochelle Dweck, an artist of Aleppine and Egyptian heritage, reimagines the synagogue in both its splendor and its shattered present through vivid, haunting color. Drawing on archival photographs and contemporary images, her work honors the memory of this sacred space, affirms the resilience of identity, and reinterprets the meaning of preservation and renewal. As history has shown, the synagogue has risen from devastation before. This exhibition invites us not only to witness what has been lost, but to imagine what may yet be restored.

Great Synagogue of Aleppo, Courtyard, 2011. A view of the synagogue’s courtyard with its iconic outdoor tebah (pulpit) and raised platform of the Hekhal HaTeqiah (Ark of the Shofar Sounding), reconstructed in the 1980s and early 1990s. ("Synagogue Aleppo," photograph by Govorkov, January 11, 2011. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.)

Floorplan of the Great Synagogue of Aleppo This floorplan of the Great Synagogue highlights the central courtyard with its tebah (pulpit), used for prayers during the summer, and the seven Torah arks along the building’s southern wall. The eastern wing was added in the 16th century to accommodate Sephardic Jews who arrived after the 1492 Spanish expulsion, while the indigenous Musta‘arabi Jews continued to pray in the western wing. (“Synagogue of Aleppo Sobernheim floorplan,” by Moritz Sobernheim, Hebräische Inschriften in der Synagoge von Aleppo, 1900, p. 280, via Wikimedia Commons.) English labels by Rochelle Dweck (based on Treasures of the Aleppo Community. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem: The Museum, 1988, p. 16.)

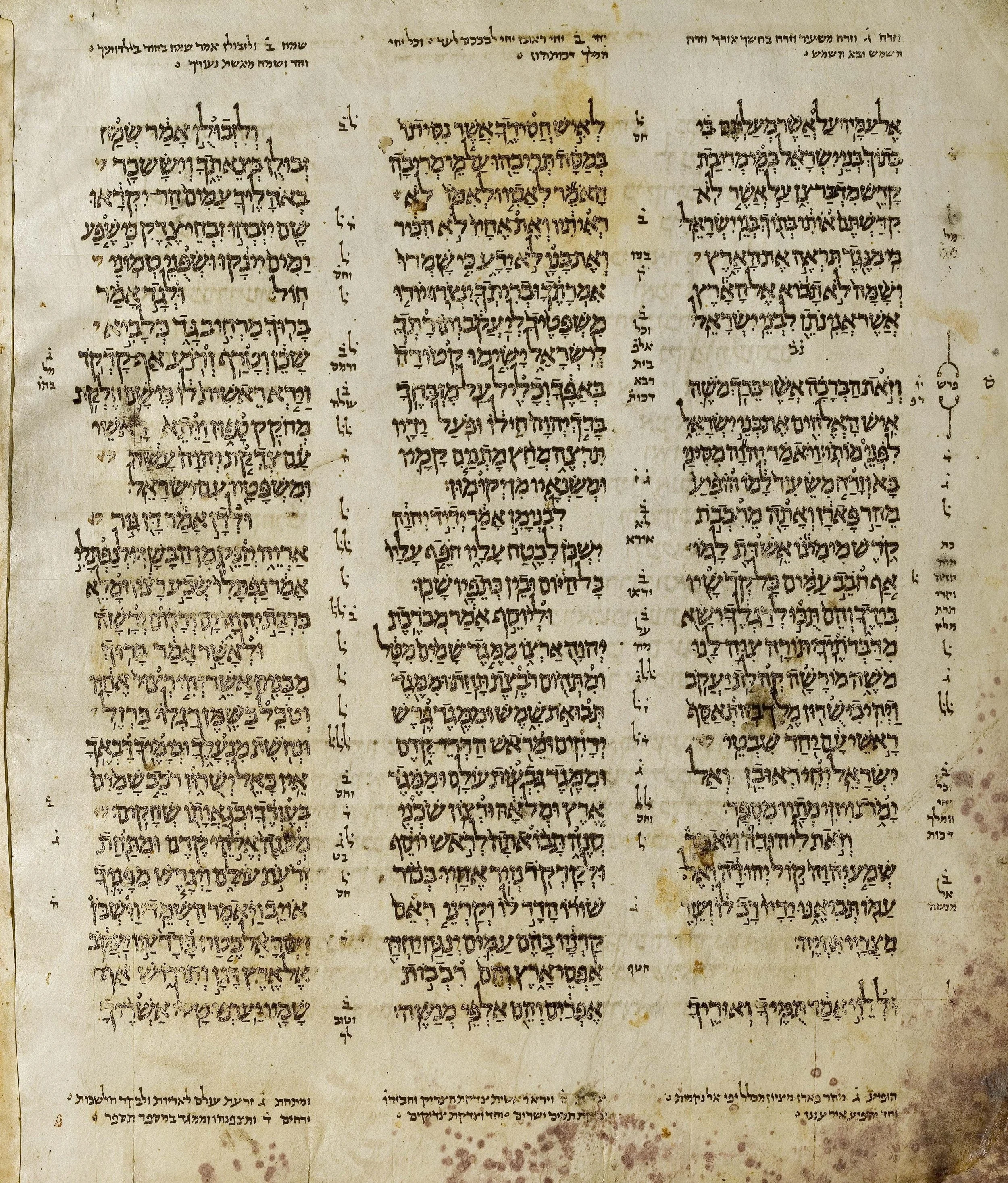

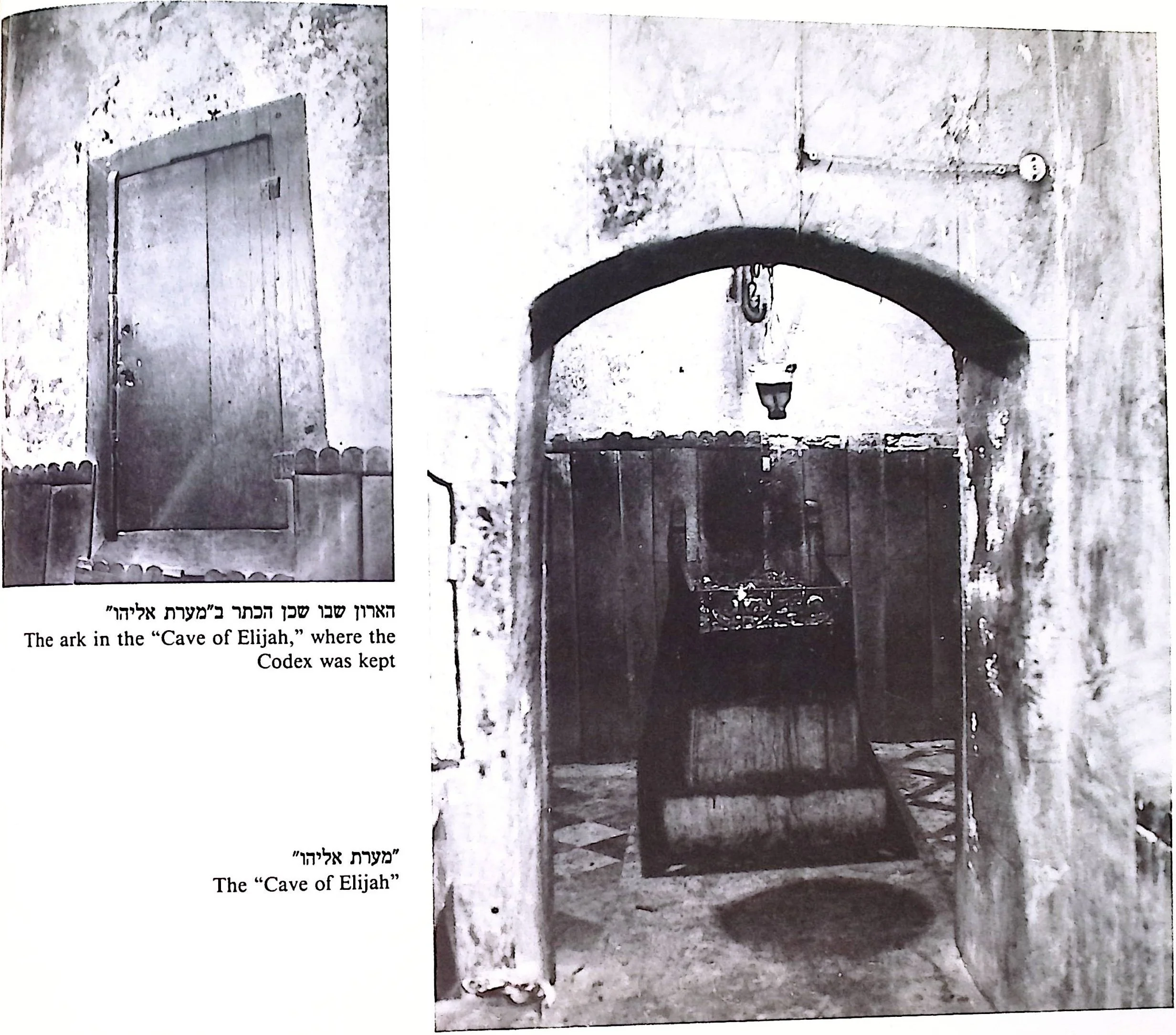

Page from the Aleppo Codex (Keter Aram Ṣoba), Deuteronomy (Devarim, Parashat VeZot HaBerakha). The Aleppo Codex is one of earliest surviving versions of the Hebrew Bible complete with Masoretic text, including vocalization and cantillation marks. Written in the 10th century in Tiberias, it was brought to Aleppo around 1375, where it was guarded in the Great Synagogue’s Hekhal Eliyahu (Ark of Elijah, located in the Cave of Elijah) for over 500 hundred years, until the riots of 1947. Approximately forty percent of the manuscript resurfaced in Israel in 1958, and is currently housed in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum. ("Aleppo Codex (Deut)," photograph by Ardon Bar Hama, 2007 for The Yad Yitzhak Ben Zvi Institute, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Al Mutanabbi Street, Aleppo, Syria, Now, painting by Rochelle Dweck, 2023, charcoal and oil on tablecloth. Rubble and devastation on the main street of the Jewish quarter in Aleppo, next to the Great Synagogue.

I. Foundations of Faith: Antiquity Through the Early Modern Era

Archaeological and textual evidence suggest that Jewish worship took place on this site as early as the 5th century CE. The synagogue’s earliest surviving Hebrew inscription dates from 834 CE. During the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, the synagogue was one of six designated places of refuge in Aleppo. However, it was ultimately destroyed in 1400 during the brutal assault led by the Turkic-Mongol conqueror Timur.[2]

Reconstruction efforts began around 1405 and culminated by 1418, transforming the older Byzantine base structure into the building that would serve generations to come. With the influx of Sephardic Jews following the Spanish expulsion in 1492, an eastern wing was added, while the indigenous Musta’arabi Jews (literally “those who live among the Arabs”)[3] continued to use the western wing for their services. Early modern travelers and photographs from the 20th century[4] help document the synagogue’s architecture, capturing a structure that was both timeless and ever-evolving.

Courtyard with Community Members, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Aleppo Central Synagogue," before 1940s, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Hallway to the Hekhal HaSatum (The Sealed Ark) with Community Members, Oblique View, Great Synagogue of Aleppo. The ark may have taken its form in 1634, after Sultan Murad IV tried to convert the synagogue to a mosque. The Jews were not allowed to restore the damaged ark, so it was subsequently sealed. For a local legend about the ark, see the footnote below. [5] (“Ernst Herzfeld Aleppo interior 2,” photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1908, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Hallway to the Hekhal HaSatum (The Sealed Ark) with Community Members, Axial View, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 02,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Hallway with Community Members, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Ernst Herzfeld Aleppo interior,” photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1908, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Congregation in Front of the Outdoor Tebah (Pulpit), Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Jews in many lands, Synagogue at Aleppo,” Elkan Nathan Adler, Jews in Many Lands, before 1905, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Leaders of the Great Synagogue of Aleppo, including Rabbi Jacob Saul Dwek and Av Bet Din Rabbi Moshe Harary (“Rabbi and officials of aleppo great synagogue,” early 20th century, via Wikimedia Commons.)

View Through the Courtyard to the Middle (Summer) Ark, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Aleppo, Great Synagogue, courtyard," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1914, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Middle (Summer) Ark Detail, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Aleppo Synagogue Ark," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1903, via Wikimedia Commons.)

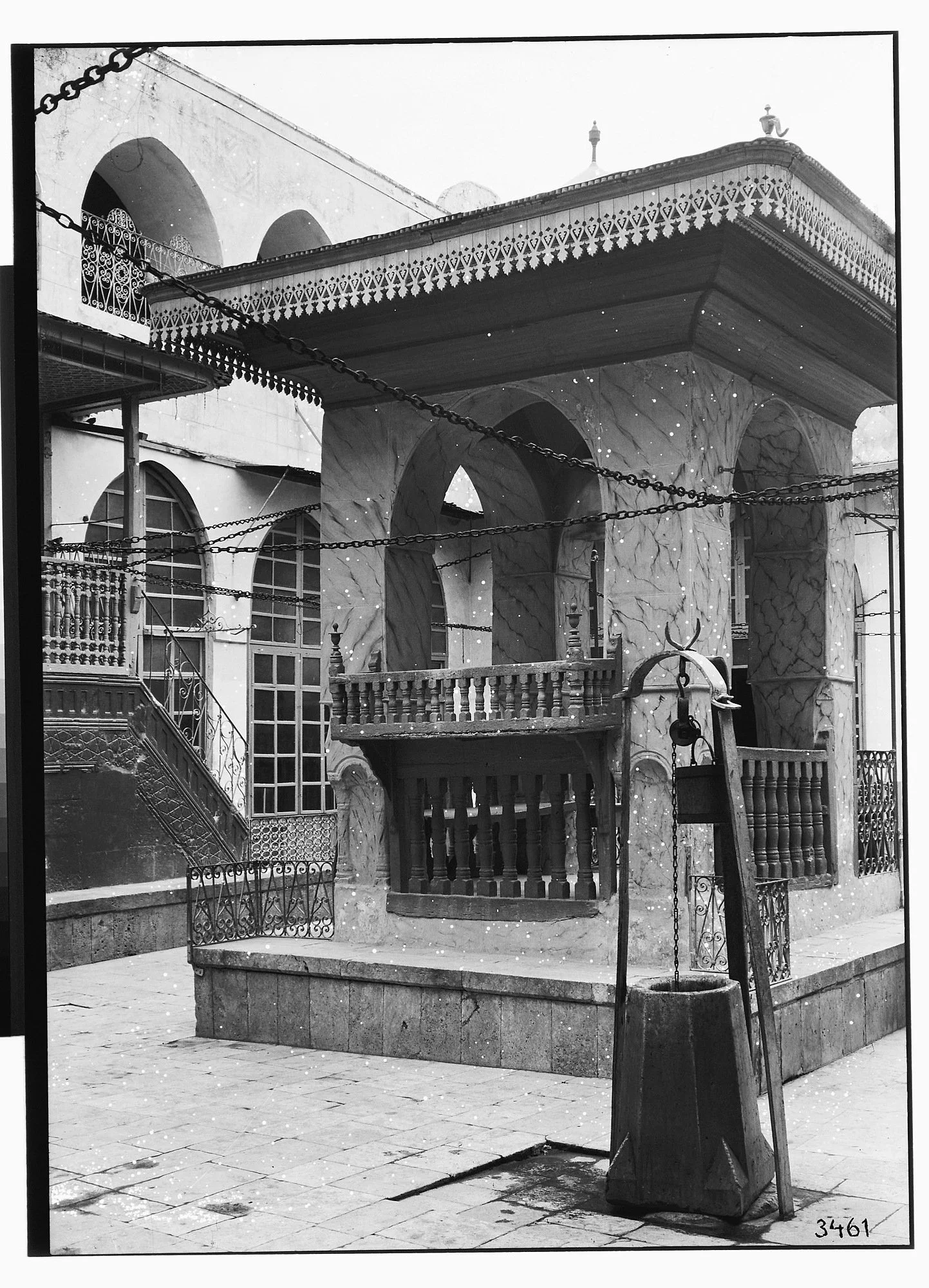

View Through the Courtyard to the Well and Middle (Summer) Ark, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Aleppo synagogue courtyard," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, between 1908-1914, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Colorized Postcard, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Synagogue Aleppo postcard colorized," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

View of the Tebah (Pulpit) and Well, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Great Synagogue, View of Central Courtyard and Tevah," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, before 1908, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., via Wikimedia Commons.)

Eastern Wing, Moritz Sobernheim Seated, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Aleppo synagogue, Moritz Sobernheim," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1908, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., via Wikimedia Commons.)

Eastern Wing, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Ernst Herzfeld Aleppo interior," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1908, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Capital in Western Wing, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Column capital Central Synagogue of Aleppo," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1908, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., via Wikimedia Commons.)

Hallway to the Sealed Ark, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Aleppo synagogue Western corridor," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1908, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., via Wikimedia Commons.)

Etching Captioned "Interior of a Damascus Synagogue" from the Jewish Encyclopedia but More Closely Resembling the Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Interior of a Damascus synagogue (flipped)," Isidore Singer and Cyrus Adler, Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906, via Wikimedia Commons.)

View of Inscriptions, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Ernst Herzfeld Aleppo 6," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1903, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Founding Inscription Detail, Great Synagogue of Aleppo. It reads זו הקבה בנה מר עלי בר נתן בר מבשר בר האדם מיגיעו וממונו שתהלך צדקה לשט (“This domed structure was built by Mr. Eli, son of Natan, son of Mubasser, son of man, through his toil and money, in the year 'tahalich tzedakah' of minyan shtarot.” See World Center for Aleppo (Halab) Jews Traditional Culture and Survival on a Promise for more regarding dating the inscription. ("Ernst Herzfeld Aleppo 3," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld (cropped), 1903, via Wikimedia Commons.)

View of Column Inscription, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Ernst Herzfeld Aleppo 5," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld, 1903, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Column Inscription Detail, Great Synagogue of Aleppo. It reads מה שהתנדב בבנין אילו ששה העמודים הר [הרב] כב מו [כבוד מורנו] אלעזר הלוי בר כב מו [כבוד מורנו] אליהו הלוי סט [סןפן טוב] מממון בניו יוסף וישמעאל והבת הכלה נע [נומה/נוחם עדן] אתשכו לש (per Sobernheim, M., and E. Mittwoch. “Hebräische Inschriften in der Synagoge von Aleppo," via the Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art), indicating the six columns of the Western Wing were donated by Eliezer HaLevi ("Ernst Herzfeld Aleppo 4," photograph by Ernst Herzfeld (cropped), 1903, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Main Entrance, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 09,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Tebah (Pulpit) Entry, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 06,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Domed Interior of Outdoor Tebah (Pulpit) Facing Middle (Summer) Ark, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 08,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Outdoor Tebah (Pulpit) Facing North, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (Photographic Archive of the Isidore and Anne Falk Information Center for Jewish Art and Life, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, courtesy of Ora and Avraham Haber, Jerusalem, before 1947.)

Hekhal HaTeqiah (Ark of the Shofar Sounding), Great Synagogue of Aleppo. Used during Rosh Hashanah to blow the shofar and for brit milot (Photographic Archive of the Isidore and Anne Falk Information Center for Jewish Art and Life, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, courtesy of Ora and Avraham Haber, Jerusalem, before 1947.)

Southern View of the Courtyard and Middle (Summer) Ark, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 15,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

View From the Eastern Wing to the Courtyard, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 05,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Eastern Wing Midrash, Great Synagogue of Aleppo. Used by the Sephardic Community (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 10,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Women's Gallery (West Side of Courtyard), Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 14,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Eastern Wing Tebah, Entry, Great Synagogue of Aleppo. Used by the Sephardic Community (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 01,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Eastern Wing Tebah, Great Synagogue of Aleppo. Used by the Sephardic Community (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 16,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Western Wing Tebah, Great Synagogue of Aleppo. Used by the Musta'arabi Community (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 03,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Ark, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 04,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Hekhal (Ark) with Sifre Torah (Torah Scrolls), Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 11,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Two Sifre Torah (Torah Scrolls), Great Synagogue of Aleppo. Fashioned in 1710, inscribed with a poem about the synagogue, each panel depicts one of the seven hekhalot (arks) (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 07,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Cave of Elijah with the Ark Where the Aleppo Codex Was Stored, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (from "Treasures of the Aleppo Community," The Israel Museum, Jerusalem: The Museum, 1988, p. 22)

Doorway with Ten Commandments and Abbreviated Priestly Blessing Above, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 12,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Cemetery, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Israel Museum Synagogue of Aleppo 13,” by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, before 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.)

II. Flames of 1947: The Partition Riots and the Synagogue’s Burning

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations approved the partition plan for Palestine. While Jewish leaders accepted it, five Arab nations – Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq and Jordan – rejected the plan. The following day, Aleppo was shut down in protest, and on December 1, violent riots erupted. Mobs looted and burned Jewish homes, schools, businesses, and places of worship, including the Great Synagogue.

The fire caused extensive damage to the building, collapsing the roof and charring ancient stonework. Though the building was not entirely lost, it was gravely wounded.[6] In the wake of the attack, the eastern section was partially restored and continued to host prayer.[7] The riots marked a turning point for Syrian Jewry: persecution intensified, emigration was restricted, and community life was fractured.[8]

Ruins of the Hekhal HaTeqiah (Ark of the Shofar Sounding), Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Central Synagogue of Aleppo 1979,” photograph by Judith Feld. The Dr. Ronald Feld Fund for Jews in Arab Lands of the Beth Tzedek Congregation The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU – Museum of the Jewish People, 1979, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Damaged Tebah, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Tevah synagogue Aleppo,” photograph by Judith Feld Carr, 1979, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Courtyard in Ruins, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Allepo1947,” source unknown but appears to be similar in style to photographs by Judith Feld, 1979, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Ruins with Tebah in Left Corner, Great Synagogue of Aleppo (“Central Synagogue of Aleppo 1979 2,” photograph by Judith Feld, 1979, via Wikimedia Commons.)

III. Quiet Restoration: 1980s Rebuilding and Diaspora Pilgrimages

In the late 1980s, members of the Syrian Jewish community in Brooklyn funded partial restorations of the synagogue. By 1992, repairs had stabilized parts of the structure, though it remained largely unused.

In June 2008, a group of Syrian Jews returned to Aleppo and held a morning prayer service within its ancient walls, reciting Qaddish and Birkat Kohanim (The Priestly Blessing), invoking memory amid silence.[9]

Main Entrance, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Central Synagogue, Aleppo, Syria," Diarna, 2008)

View Through Main Entrance, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Central Synagogue, Aleppo, Syria," Diarna, 2008)

Northeast View of Restored Courtyard, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Al Bandara synagogue," photograph by Michael Korn, Google Maps, 2020)

Tebah, Restored, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Al Bandara synagogue," photograph by Sami Zidan, Google Maps, 2022)

Courtyard, Restored, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Central Synagogue, Aleppo, Syria," Diarna, 2008)

Tebah, Restored, Detail, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Central Synagogue, Aleppo, Syria," Diarna, 2000s)

Middle (Summer) Ark Detail, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Al Bandara synagogue," photograph by Moussa Samuel, Google Maps, 2019)

View Through the Arches, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Al Bandara synagogue," photograph by Moussa Samuel, Google Maps, 2019)

View Through Arches with Chandelier, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Central Synagogue, Aleppo, Syria," Diarna, 2000s)

View from Eastern Wing Towards the Entrance, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Al Bandara synagogue," photograph by Moussa Samuel, Google Maps, 2019)

View to Hekhal HaSatum (The Sealed Ark) with Overgrowth, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Al Bandara synagogue," photograph by Michael Korn, Google Maps, 2020)

Cemetery with Overgrowth, Great Synagogue of Aleppo ("Central Synagogue, Aleppo, Syria," Diarna, 2008)

IV. War and Ruin: The Syrian Civil War of 2016

The outbreak of civil war in Syria brought renewed devastation to Aleppo. By 2018, street-level images[10] revealed the synagogue’s courtyard in ruins — its walls crumbling, its cemetery overgrown, and its future uncertain.

Artist Rochelle Dweck re-envisions the synagogue in its glory and its current state. All images immediately below are courtesy of the artist.

Great Synagogue of Aleppo, Syria 4, 2022, charcoal and oil on paper. View through the northern archway of the courtyard to the western wing.

Great Synagogue of Aleppo 2, 2022, oil on paper.

Great Synagogue of Aleppo, Syria 3, 2022, charcoal and oil paint on paper

Courtyard, 2017, woodcut print on BFK Rives paper.

Menarsha Synagogue, 2021, Intaglio print on cotton rag paper. Though located in Damascus, the Al-Menarsha Synagogue offers a glimpse into what Syrian synagogue interiors may have looked like when they were still in active use.

Heichal Hasetoom, 2021, insulation foam, papier-mâché, gesso, rocks, dirt, acrylic, tempera. Crown of the Sealed Ark with an abbreviated form of the Ten Commandments.

Chief Rabbi Haim Shaul Dweck, HaCohen, 2023, charcoal and oil on paper. Artist’s great great great great grandfather, believed to have possessed healing powers.

Great Synagogue of Aleppo, Syria 6, 2023, ink and oil pastel on plastic. Ruins of the eastern wing.

Aleppo Cemetery, Syria 1, 2022, oil and charcoal on cardboard.

The Great Synagogue of Aleppo Courtyard 5, Now, 2023, oil on canvas. View of the southwest corner of the courtyard.

V. Sanctuary Without Walls: Legacy Across the Diaspora

Though its stones have been scattered and scorched, the Great Synagogue’s spiritual legacy endures. Syrian Jews from Aleppo have built vibrant communities across the globe — in Brooklyn, Deal (NJ), Mexico City, São Paulo, and Israel — carrying with them the melodies, customs, and memories once contained by these walls. The synagogue, now silent, lives on in its spiritual descendants and the "daughter synagogues" they have established.

Even in ruin, the Great Synagogue of Aleppo has not been forgotten. Its form lives on — meticulously documented in photographs, captured in artworks like the paintings in this exhibition, and reimagined in models, including a replica at the ANU Museum of the Jewish People[11] and a virtual reality reconstruction at the Israel Museum.[12] These acts of preservation are not only tributes to the past but may also be gestures toward the future. The synagogue has quite literally risen from ashes before. With its details enduring in memory and record, may we yet see the day when it is rebuilt — not only in image, but in stone.

Interior of the Ades Synagogue, Jerusalem ("Inside Ades Synagogue," photograph by Ori lubin, 2005. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.)

Courtyard [of The Great Synagogue of Aleppo], woodcut by Rochelle Dweck, printed on BFK Rives paper, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Model of the Synagogue of Aleppo at the ANU Museum of the Jewish People, Tel Aviv ("Tel Aviv-Yafo P1100393 (5155627794)," photograph by Ricardo Tulio Gandelman, 2010. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.)

“Back to Aleppo: A Virtual Reality Tour of the Great Synagogue” at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (Curated by Revital Hovav, designed by Ariel Armoni, June 16, 2022 - June 29, 2024, Israel Museum.)

References

[1][2] “Central Synagogue of Aleppo.” Wikipedia. Accessed on May 1, 2025.

[3] “Musta’arabi Jews.” Wikipedia. Accessed on May 1, 2025.

[4] Many of the historical photos of the synagogue before the 1947 riots are from two sources: (1) The Ernst Herzfeld papers, including photos by Ernst Emil Herzfeld (1879-1948), German archaeologist, philologist, geographer and historian in the field of Near Eastern Studies, and (2) Mrs. Sarah Shammah, a native of Aleppo who moved to Jerusalem and visited the synagogue in autumn of 1947, hiring a photographer to document the synagogue shortly before it was vandalized and desecrated. Mrs. Shamah’s photographs were made available by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

[5] Leah Bornstein-Makovetsky, “The Political and Social Status of the Jews of Aleppo, 1517-1800,” in Aleppo Studies: the Jews of Aleppo: vol 2: Their History and Culture, eds. Yom Tov Assis, Miriam Frenkel, and Yaron Harel (Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 2013).

Rabbi Abraham Dayan relates a different legend in his book ״הולך תמים ופועל צדק״ ("Walking Innocently and Doing Righteousness,” 1850, p. 68r via Hebrew Books.org. According to "an old man," the community was celebrating Simḥat Torah when their joyous festivities drew the attention—and envy—of a local official who sought to convert the synagogue. That night, he and his men stayed inside the building, when a large venomous snake coiled around his neck. The elder of the court was summoned and asked whether he had harbored evil intentions toward the site. The official confessed and, in repentance, pledged to repay the community with double kindness. The elder then turned to the snake and said, “Return to your place,” at which point the snake returned to the ark. From that day forward, the ark was sealed off, as the community believed the snake was a divine messenger.

[6] Most photos from this period are from Judy Feld Carr, a Canadian musicologist who helped smuggle over 3,000 Jews out of Syria between 1975 and 2000. For more details see Judy’s story - the heroism of a Canadian who smuggled Jews out of Syria.

[7] Silvera, Carol. “The Great Synagogue of Aleppo.” CUNY Academic Commons. Accessed on May 1, 2025.

[8] “Restrictions and Violence.” Sephardic Heritage Museum. Accessed on May 1, 2025.

[9] “Central Synagogue of Aleppo,” Wikipedia.

[10] "Street View image of the Al Bandara synagogue, Aleppo." Google Maps. Photograph taken Feb 2018.

[11] “Central Synagogue of Aleppo,” Wikipedia.

[12] Friedman, Matti. “The Lost Synagogue of Aleppo.” Tablet Magazine. Accessed May 1, 2025.

![Column Inscription Detail, Great Synagogue of Aleppo. It reads מה שהתנדב בבנין אילו ששה העמודים הר [הרב] כב מו [כבוד מורנו] אלעזר הלוי בר כב מו [כבוד מורנו] אליהו הלוי סט [סןפן טוב] מממון בניו יוסף וישמעאל והבת הכלה נע [נומה/נוחם עדן] אתשכו לש (per S](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6034089f3800100c8a8d5001/7fe623f0-1cfd-4389-9ab3-7140e4762fb2/Ernst_Herzfeld_Aleppo_4.jpg)

![Courtyard [of The Great Synagogue of Aleppo], woodcut by Rochelle Dweck, printed on BFK Rives paper, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6034089f3800100c8a8d5001/4477122a-6b3f-4f9e-b1b8-8df7d172415a/Screenshot+2025-05-07+at+2.30.17%E2%80%AFAM.png)